The future rarely comes early. Especially in the world of wine, where tradition tends to hold sway. DOC Luján de Cuyo (Denomination of Controlled Origin), however is an excellent example of a temporal paradox.

DOC Luján de Cuyo was inaugurated in 1989 with the goal of protecting a heritage that was in decline: the best vineyards of Luján de Cuyo, especially those planted with Malbec, had been shrinking since the 1970s. The vision of the handful of producers who made it happen was as bright and clear as a spring morning: if they didn’t do something to maintain their viticultural heritage, they’d be regretting it sooner or later. And so, in 1989, Chandon, Lagarde, Luigi Bosca, Nieto Senetiner, Norton and Otero Ramos came up with the idea of a Denomination of Origin for Luján de Cuyo.

“Those who created the Luján de Cuyo DOC were genuinely visionary, they were ahead of their time. It’s important to recognize that those who worked and still are working on the Denomination of Origin were motivated by an overriding interest in preserving and honoring the old vineyards of Luján de Cuyo. The existence of a D.O.C. protects producers as it enhances the status of their vineyards, making them a part of the national heritage, preserving and valuing old vines, and the consumer, who has the quality and identity of the product they’ve purchased guaranteed,” says Roberto de la Mota, the current President of the DOC.

DOC Luján de Cuyo

In 1991 the first Malbec Luján de Cuyo DOCs appeared on the market, representing the first DOC on the continent. They were no less than 30 years ahead of the rest of the wine business. What does that mean? It’s simple: in the 1990s Argentina started to export wines en masse and Malbec turned out to be key to the process, but its place of origin didn’t seem to matter too much. Consumers just fell in love with Malbec full stop; the country’s different regions were forgotten for a little while.

Change soon followed. In the 2000s, Malbec started to be planted everywhere: from Agrelo in Luján de Cuyo, to Altamira and Gualtallary in the Uco Valley. Malbec fever drove up the number of hectares under vine from 10,000 when the situation was alarming producers, to more than 46,000. Little of this planting had much to do with concepts like DOCs, or so it seemed.

Luján had a mission

That was when the past revealed itself to be have been a step into the future. The stylistic muddle that came with the Malbec explosion, in which the same variety was producing wines that were skinny and juicy alongside others that were spicy and voluptuous and still more that were rich with a chalky texture, eventually worked itself out into clear, regional characters. Malbec from Luján tends to be ripe, velvety and voluminous.

The Luján de Cuyo DOC, meanwhile, was sleeping the sleep of the precocious. Only a few of the producers still had DOC wines on the market but they sold well. Norton, Nieto Senetiner, Lagarde and Luigi Bosca, the founding wineries, sold their Malbec DOCs in Argentina, counting on the prestige that came with their history and elegant style.

But temporal paradoxes need to work themselves out eventually. Following the revolution in Malbec styles, the Luján de Cuyo DOC is finally coming into its own: place, style and flavor is the mantra of the current scene. And so the producers decided to revive the concept. Where in the 90s, it was an initiative driven by producers looking to protect their heritage, this time it’s experts, oenologists and agricultural engineers looking to properly define a regional style.

The Luján de Cuyo DOC was an answer to a crucial question nobody at the time had really thought to ask. In addition to protecting vineyards, it also showed how a region can establish a flavor in the minds of consumers. The former goal was achieved and then some, but now the second was coming into its own.

As Walter Bressia, the oenologist at Bodega Bressia explains: “The Denomination of Controlled Origin was created to establish a privileged place for Malbec on the global scene, a profile that occurs naturally in this region. We wanted to give the variety a distinctive character, and now it’s earning praise from all across the world.”

What is a Malbec DOC wine?

The Malbec must come authorized vineyards in Luján de Cuyo, where the vines need to be at least 10 years old, with at least 5000 plants per hectare and maximum yields of 10 tons per hectare, aged for at least a year in barrels and for two years before it goes on the market—as stipulated under the terms of the DOC—so as to guarantee a specific flavor profile.

New producers that have joined the Luján de Cuyo DOC include Bressia, Casarena, Mendel, Vistalba and Trivento, and now they are teaming up with the six founders to being new life to the project: in addition to establishing a regional profile, they are beginning to define the wines by district.

Paula Pulenta, at Bodega Vistalba, says: “Being part of the Luján de Cuyo DOC makes us excited and enormously proud. We are sharing our variety with the world; Malbec, the characteristics of our terroir and the way we produce. We are expanding and reaffirming a concept that, in a competitive industry like ours, we believe makes a very significant difference.”

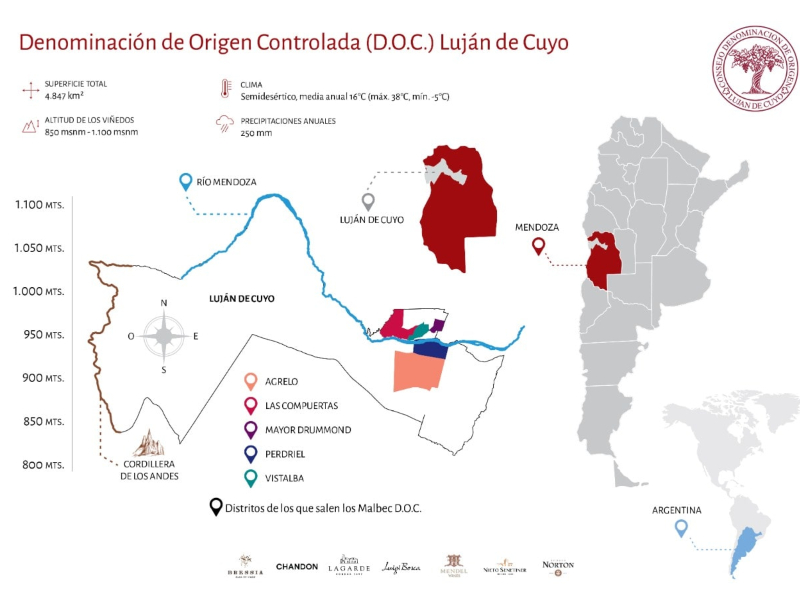

Other producers are in the process of joining as well. In the medium term, we will see the DOC narrowing its labelling down from Luján de Cuyo to districts such as Las Compuertas, Drummond, Perdriel and Agrelo. Each of them, which now have legal recognition, is producing its own flavor.

If there’s something that producers have learned since the 2000s, it’s that the more specific the terroir, the more distinctive the expression. This is what the Uco Valley has shown, where producers are producing wines from specific parcels and patches of soil.

And there’s plenty of scope for doing the same in Luján, where each district has a different soil profile even though the climate and altitudes tend to be similar: on the shores of the Mendoza River, in Las Compuertas, Vistalba and Perdriel for instance, different sizes of gravel are mixed with lime and clay; to the south of the river, in Agrelo, one finds deep clay soils, to the east, the soils are shallower and stonier, with the exception of the Sierras de Lunlunta, which have their own unique profile.

And so, the geography is reflected in the wines produced within it, and this is now backed up by regulations that define these origins. The Luján de Cuyo DOC is continuing to broadcast its message into the future.